Types of Evidence

The evidence that forms the bedrock of a scientific argument is arguably its most critical component. If students are to evaluate the opinions and arguments of others, then they must be well equipped to judge the quality of evidence.

Students must be exposed to the concepts that scientists use to assess the value of evidence, such as repeatability, experimental design, and sample size. These concepts and more are introduced in a friendly manner by Covitt et al.:

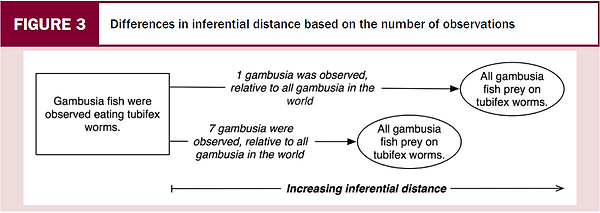

One important feature of evaluating evidence is judging whether the data supports the conclusion drawn. Even with perfectly reliable data, misleading conclusions can be drawn by making leaps of logic that are too large. This idea is the basis of the work by Brodsky et al., which coin the term “inferential distance” to describe the size of the conceptual leap needed to connect evidence to the conclusion drawn. In conclusions that are strongly connected to the evidence, the inferential distance should be small.

Inferential distance can be affected by many factors already listed in the Covitt paper, including sample size and how closely a model matches a natural system.

Brodsky et al. described their concept in the context of a class terrarium for middle school students within which students were trying to identify ecosystem interactions. The concept of inferential distance, however, can be applied more broadly by giving students another tool for judging evidence. The visual nature of the comparison can help students to make their conclusions more concrete.

Equally important to addressing the quality of evidence is learning how to collect solid evidence. Lawson reimagines the traditional scientific method (a poster superstar of middle and high school science classrooms everywhere) in an attempt to make more explicit the logical steps involved. He imagines four major stages:

-

Abduction: a hypothesis is generated based on an analogy to some other already explain observations. The explanation is ‘abducted’

-

Retroduction: the hypothesis is tested using an if/then/therefore process. If A is true, then B must happen, therefore A is possible or impossible.

-

Deduction: the hypothesis is used to create some predictions about future observations to test is validity.

-

Induction: use the collected evidence to draw a conclusion

In my view, Lawson’s ideas can be simplified into

-

Abduction – generate an explanation based on prior knowledge

-

Retroduction – follow your initial explanation to its logical consequences

-

Deduction – make testable predictions based on these consequences

-

Induction – draw a conclusion (and return to earlier steps as needed)

Perhaps the simplest take-away from Lawson’s work is his heavy use of the if/then/therefore structure. Students can make use of this simple logical construct to make conclusions that are always supported by evidence. The author provides an example:

“Testing the dissolving-CO2 hypothesis: If . . . the oxygen is converted to carbon dioxide, and . . . the carbon dioxide dissolves in the water, then . . . the inside pressure should be less than outside causing water to rise. And . . . the water did rise. Therefore . . . the hypothesis is correct due to rising of the water. “

Overall, the Lawson model is shown in the following figure:

References:

Brodsky, Lauren, Andrew Falk, and Kevin Beals. 2013. HELPING STUDENTS EVALUATE THE STRENGTH OF EVIDENCE IN SCIENTIFIC ARGUMENTS: Thinking about the inferential distance between evidence and claims. Science Scope 36, (9) (Summer): 22-28, http://search.proquest.com/docview/1412868115?accountid=15115 (accessed February 20, 2015).

Covitt, Beth A., Cornelia B. Harris, and Charles W. Anderson. 2013. Evaluating scientific arguments with slow thinking. Science Scope 37, (3) (11): 44-52, http://search.proquest.com/docview/1458259998?accountid=15115 (accessed February 16, 2015).

Lawson, Anton E. 2010. Basic inferences of scientific reasoning, argumentation, and discovery. Science Education 94, (2) (03): 336, http://search.proquest.com/docview/194929143?accountid=15115 (accessed February 17, 2015).